Compared to the thousands recently killed in the cities and towns of Nepal, the 18 climbers and Sherpas lost on Mt. Everest in an avalanche caused by the first of recent earthquakes there is a small number. But it still rates as the worst annual death toll so far on the mountain, topping even last year’s record of 16 Sherpas lost in an avalanche that, like this one, shut down the climbing season for the year.

Statistically speaking, however, Everest has actually gotten much safer in the past 15 years. In a 2014 article he wrote for the New Yorker, Jon Krakauer (of Into Thin Air acclaim) stated that from the first British expedition to the mountain, in 1921, until 1996, there were 630 summits and 144 deaths, or an average of one death for every four successful summits. From 1996 – 2014, he said, there were 6.241 summits and 104 deaths, or an average of one death for every 60 successful summits. (Or one death for every 88 successful summits, if you don’t count the Sherpas, who endure far greater risks than the “client” climbers and professional guides.)

Krakauer is a very reliable source. But hard facts on this subject are surprisingly difficult to nail down. A website called everesthistory.com, which offers a list of successful summits from 1953-1996 … by name, exact date, expedition name, nationality and route by which the summit was reached … lists 956 successful summits during that time. And in 2013, a Time magazine article estimated the total number of people who had summited Mt. Everest to be closer to 3,500 than Krakauer’s 6.241 estimate.

So I have no idea exactly how many people have summited Mt. Everest to date, or what the precise death-to-summit ratio is. But by any measure, that ratio has gotten much better. Some reasons for the decrease in risk include the fact that guiding companies now have ropes and ladders set for climbers along the routes, and each season leaders try to set routes with less likelihood of an avalanche. Climbers now use supplemental oxygen far more than they used to, and many also prophylactically take a drug called dexamethasone to ward off altitude sickness and high-altitude edemas. Weather forecasts are more accessible and accurate than they used to be. And many climbing companies now encourage their clients to acclimatize on safer routes and mountains first, so they don’t have to make as many danger-laden trips across the Khumbu Icefall above base camp on Everest.

That increase in safety statistics, and ease of ascent, no doubt accounts for one of the risk factors that is actually increasing on the mountain: the sheer number of climbers attempting the summit on any given day, let alone any given year. In 2010, more climbers summited on a single day in May than had reached the top of Mt. Everest from 1953 (when Sir Edmund Hillary first accomplished the feat) through 1983 … combined. (Source: The Himalayan Database)

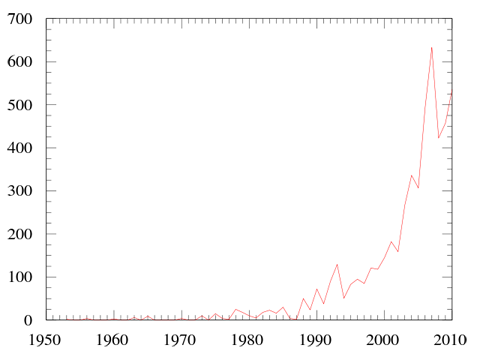

Here’s how that exponential increase in climbers and summits looks on a graph:

(Source: Wikipedia)

The biggest danger of those exponentially increasing numbers is that they create hazardous bottlenecks at key spots high on the mountain, where climbers may have to wait hours to climb a narrow section of rock. That means they’re exposed to the elements for much longer, and it often pushes them up against safety “turnaround” time deadlines. In addition to those risk factors, the mountain is also ill-equipped to absorb the garbage and sewage of that many people (the subject of the aforementioned Time article ).

But those numbers also beg the question: is Everest still the realm of great adventurer-explorers? The obvious answer is … no. At least, not compared to the exploits and experiences of George Mallory, Edmund Hillary and their expedition-mates.

I just finished reading an excellent, if long, account of the initial attempts to conquer Everest, in the early 1920s. Written by anthropologist and National Geographic “Explorer-in-Residence” Wade Davis, Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest looks at not only the day-to-day details of the expeditions, but the entire backstory of the explorers’ lives. And reading about their exploits–exploratory forays that never accomplished their goal, and resulted in the loss of not only Mallory and his climbing partner Sandy Irvine, but 11 others associated with the three expeditions (1921, 1922, and 1924)–makes the current climbing scene on Everest look like a scripted Disney ride by comparison.

In my last post, I talked about the difference between exploring territory where you have not gone before and exploring territory where nobody has gone before. George Mallory and his compatriots were definitely in the latter category, and that’s what makes the book so compelling. Nepal was a “closed” country back then, and Tibet was only marginally accessible to foreigners. One of the reasons nobody had attempted the mountain before, borders and permissions aside, was that there wasn’t even a map of the region to show where the mountain was or how to get to it.

The “discovery” of Mt. Everest by the western world didn’t happen until 1856, when a surveyor in India, working more than 108 miles away from the mountain, determined this particular unnamed peak to be 29,002 feet tall, or more than a thousand feet higher than any other known mountain. (When Everest was officially measured by satellite technology, many years later, the result was only 28 feet off that original measurement.) Explorers made a few forays into the region in the early 1900s, but then World War I broke out, and it wasn’t until 1919 that British eyes turned again to the idea of Everest.

Mallory and company had to approach the mountain from its North Face, because Nepal was closed to them. And they spent the months of the 1921 expedition just trying to figure out how to get to the mountain. The only way to determine that a route was a dead end was to take it–in all kinds of bad weather, as it turned out, because Mallory and company only learned the hard way that the monsoon season begins by mid-June in the Himalaya. Today, of course, everyone knows that the “season” to climb Everest is in late April or May.

In addition, there was almost no understanding of the physiological effects of high altitude at that time, and the use of supplemental oxygen was experimented with for the first time on the 1922 expedition–but by only one climber named George Finch. The rest thought it was either cheating or nonsense, and the oxygen equipment they did have was cumbersome and cantankerous. The men’s climbing outfits were cumbersome and ill-suited for the cold of Everest, as well, and the effort of trying various routes in the hopes of finding one that was passable was exhausting. Really, the surprising thing is that more of the men didn’t perish, and that they got as close to their goal, over a mere three years, as they did. Along the way, however, expedition members did succeed in gathering huge amounts of new data on flora and fauna and geographical topography.

It was, in other words, an effort of true exploration. The three trips “into the silence” were blind forays into the unknown, expanding the world’s knowledge and understanding of that realm through the effort. But the knowledge came at the price of staggering levels of risk, discomfort, and difficulty.

Davis believes that the motivation driving the conquest of Everest was a search for redemption and an uplifting victory after the atrocities of World War I. And for Britain, the Alpine Club and the other backers of the expeditions, that’s undoubtedly true. But what about the men who endured those risks and discomforts first-hand?

After reading Davis’s book, I think the climbers would have taken on the risks of Everest even if they hadn’t been in the war. All of them inherently loved climbing and adventure, and Mt. Everest was something akin to the holy grail of mountain climbing. “The highest peak in the world.” Hard to argue with the lure of that. In that sense, they were no different than everybody else who’s dreamed of Everest.

But two things differentiated them. Today, the climbers of Everest are not contributing anything new to the world. They are not part of something bigger than themselves, the way the expeditions of Mallory were. And the achievement is not landmark in the same sense. It’s personal, not historical.

Second, the climbers who made the summit attempts with Mallory were some of the most talented and dedicated climbers in the British Empire. They had taken great risks to learn the skills they already had, and they knew what they were attempting might turn out to be impossible, or lethal. And they signed on, knowing that the attempt would require great dedication and sacrifice … just as elite athletes who want an Olympic Gold medal do. Feats of greatness, whether they be Olympic records or the first summit of Mt. Everest, do not come easily They require years of difficult, disciplined effort. That’s why we respect those people who make the sacrifices to achieve them.

Most of us would love to win an Olympic medal, of course, but very few of us have the talent, let alone the level of passion and determination required to put in the years and effort to achieve that level of “greatness.” We have to settle for lesser rewards. And that should be okay with anyone who wants a life more balanced or diverse than what greatness requires.

And yet, people–including relative novices–still go to Everest in search of greatness. But I’m not sure greatness is to be found there anymore. Achievement, yes. Today’s summiters of Everest still have to train, and still take on some level of risk. But they are more like marathoners than explorers, with the question not “can this be done,” but merely “can I do it?” –and with the caveat of requiring a whole lot of assistance to make even that achievement possible.

In tacit recognition of this fact, the Himalayan Database actually lists three separate eras for Everest: The Expeditionary Period, 1950-1969, The Transitional Period, 1970-1989, and The Commercial Period, 1990 until now. I would actually add one more: The Exploratory Period, 1921-1949. But the point is, there is a difference between being guided up a mountain and exploring routes on your own, just as there’s a difference between flying with an instructor and flying solo. The level of talent, competence, work, and risk are far higher on your own. So, of course, are the rewards.

The bottom line, however, is that while bits of glory can be found in many places, true greatness is found in far fewer. There are no shortcuts to it. And–as the tragedy of Mallory and his compatriots reminds us–it often comes with a very steep price attached, indeed.