One of the reasons I like physical adventure (and write about it so often), is that it provides such rich source material for important life lessons. Life lessons can be found anywhere, of course, and adventure comes in many forms beyond physical pursuits. But there’s something about a physical challenge that tends to present the lessons in a more visceral fashion, with tangible and generally immediate consequences, that makes the lessons harder to miss.

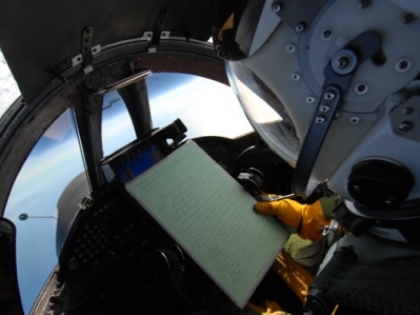

Last week, for example, I was flying with a friend in Northern California. She’s a fairly new pilot, with a Cessna 172 she keeps up at the Napa County Airport. We’d gone out for a fun lunch adventure and were returning to Napa in time to pick up her kids from school. The air traffic controller at Napa Airport put us on what they call a “straight-in” approach to the north-south runway there, landing to the south. So we were lined up with the runway several miles to the north of the airport but descending at a steady rate.

We’d already descended below the ridge line immediately to our left (east) and were about four miles from the airport when the controller told us to make a left 360-degree turn (or, a full circle to the left) to allow the controller enough time and space to land another plane in front of us. I looked to the left, where the ridgeline was pretty close.

“We’re not making a left 360 [degree turn] here,” I told my friend. “Ask for a right 360 instead.” She asked, and the controller agreed. So we did a complete level circle to the right, then rejoined our descent path to the runway again. We’d gotten a half mile closer when the controller called us and told us to make another right-hand circle. When you’re low to the ground and slowing up for landing, diverting from your path is a bit of a challenge. Doing it once is asking a bit from a pilot. Doing it twice is asking a lot.

But pilots are trained to please controllers. Our default response is to do what they ask, because that’s what we assume they need in order for traffic to flow smoothly and safely. Pilots also take pride in their competence. Like many professionals, we have a strong desire to prove that we can do what is asked of us. So my friend and I did another right-hand turn and rejoined our descent path once again.

We’d gotten another mile closer to the airport when the controller called us again. She’d just cleared a big business jet–which wasn’t even talking to the tower when we’d started our approach–to land on the same runway we were approaching. The business jet was coming from the south, flying north up the east side of the field. We were north of the field, heading south. Just as the business jet turned right, toward the runway (so, heading toward us), the controller told us to make a third right-hand circle, so she could land the jet ahead of us.

In addition to asking a pilot to make three circles on an approach (really bad) … if you’re tracking this unfolding drama with hand movements or doodles, you’ll also realize that the controller was telling us to turn west and then north just as the jet was turning east and then south. Or, in other words, head-on into each other’s path.

It doesn’t take a high-time pilot or rocket scientist to realize that this was, inherently, a really BAD idea. I could see the business jet getting bigger in the windscreen as it descended toward us. Briefly, I debated whether I should tell my friend to just head straight west until the jet was safely past us. But that might put us in the path of other arriving traffic. So I told her to make the turn to the north as smartly as she could and then just keep heading north. When I estimated the jet was well past our position, I told her to finish the turn back to our original approach heading. We did a modified descent angle that kept us higher than the jet’s path, to keep us out of its “wake” (like the wake of a boat, but which can turn a small airplane caught in it upside down because of how it twists in the air), and touched down safely.

All ended well. But in retrospect, I should have made a different call. About the time the controller asked for the second circle, or certainly the third circle right into the path of a big business jet, I should have told my friend to simply tell the controller … “Unable.” Pilots are allowed to answer “unable” to controllers any time they feel a controller’s demands are going to put them in a position they don’t feel is safe, or within their ability to manage. If she’d said “Unable,” the controller would have had to come up with a different solution–tell the business jet to fly a little further north before turning, to give us time to land, or maybe tell us to “go around,” and do another complete approach.

The controller might not have been happy about it, but either of those two options would have been safer and better than us turning a crazy third circle, low to the ground, and frantically trying to stay out of a business jet’s flight path. So why didn’t my friend take that option, and why didn’t I think to tell her to take it?

I think it’s the same reason that most professionals don’t look their bosses in the eye and say “Unable” when the back-breaking-straw request for additional effort, or a shorter time frame, or another work load item gets added to the list. If you’re a pilot, or a working professional, chances are you’re achievement-oriented on some level. You pride yourself on competence; on the ability to show that no matter what anyone throws at you, you can come through for the team. People are counting on you, and you want to prove yourself equal to the task. And, on some level, you probably do some quick calculations and figure, well … if you work the weekend, if you stay late, if you blow off your gym workout, if you don’t go to your kid’s soccer game, if you tell your spouse you can’t make dinner, if you just go without some sleep … you can do it. It’s not impossible.

But just because something is possible doesn’t make it reasonable, or smart, or sustainable. It also may have a hidden or long-term cost that is actually more negative than any benefit that will accrue from doing the requested task. It also, by the way, sets a bad expectation and precedent.

When I first started working for myself, I was living on the west coast, but I had clients on the east coast. When they’d call–even if it was 4:00 am my time, I’d spring out of bed and answer the phone. I figured I needed to be available to my clients to be a “good” contractor. My mother finally pointed out to me that not only was I probably not at my mental best, 20 seconds after being woken from a sound sleep, but that by answering the phone, I also was training my clients that I would answer the phone whatever time they called. I went out and got phones I could turn off the very next day.

I got a second insight into the power of “Unable” when my father fell off an extension ladder, 15 years ago, and ended up in a coma, in the hospital, where it was a number of days before it was even certain that he would live. I was in the middle of a big book contract at the time. I had a chapter due three days after his accident, and the entire manuscript was due–with a no-kidding, do-or-die publishing deadline (it was a commemorative book, so date-critical) just five weeks later. When it became clear that I was going to have to stay on the East Coast for several weeks to take care of my dad, I called my editor. I said I was very sorry, and I’d completely understand if they cancelled my contract, but I could not make the deadline.

Much to my surprise, the sky did not fall. The once non-negotiable deadline became surprisingly negotiable. I turned in the manuscript 6 weeks late, and we made the publishing date anyway.

Granted, that was an extreme situation. But since then, I’ve discovered that a lot of non-negotiable work deadlines and demands are surprisingly negotiable when you firmly but politely say you’re very sorry, but you can’t meet those demands and still be effective or do a good job.

Of course, you do have to use judgment when playing the “Unable” card. It’s also important to remember that when pilots say “unable,” they’re really starting a conversation with a controller about better options, not drawing a stubborn, final line in the sand. So it helps to follow up an “unable” response with some ideas of alternative and more feasible options. But draining or stretching ourselves too far, no matter how much people tell us they need us to do that, can end badly: burnout, poor performance, mistakes, divorce, general unhappiness … or, in the case of airplanes, real tragedy.

Acknowledging our limitations is as important as knowing our strengths. And even if our bosses or clients aren’t air traffic controllers, we all, in the end, have the responsibility of keeping ourselves in a place where we can continue to operate sanely, safely, effectively, and with some margin in reserve.

Next post: More on the Power (and Virtue) of Saying “No”

Previous post: Where Does Vision Come From? (My TV interview thoughts)

I sat in a classroom several years ago while an aviation attorney spoke to us about the most important word a pilot must learn…Unable.

He reminded us that the pilot, not the controller, was in command of the aircraft and would most certainly be held responsible if things went poorly as a result of blindly following ATC “commands”. The determination of what constitutes safe operation of the aircraft belongs to the pilot alone. That may, indeed, vary with the experience and/or tools at hand and that is as it should be.

Excellent article, well said!

Well written and very important for training and new pilots. It’s common knowledge within General Aviation that learning to communicate with the control tower is most intimidating. Realizing that you can and should, on occasion, “just say no” is helpful.

signpilot