So, I had two other topics I was going to write a post on today – thoughts about some of the costs of adventure. But I got a piece of news in my in-box last night that’s pushed those topics aside for today.

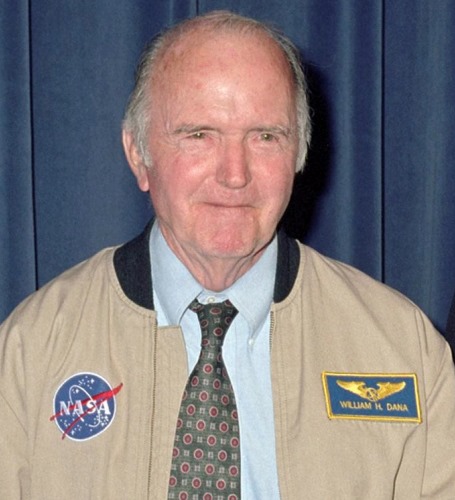

Bill Dana, a retired NASA aeronautical engineer and test pilot (or research pilot, as they proudly call themselves) died yesterday. He didn’t die in a plane crash; he was 83, and he’d been ill for some time. But his passing still makes me sad, for I have lost a kindred spirit in the world.

Ever since Tom Wolfe wrote The Right Stuff about those early Air Force test pilots who broke the sound barrier and went on to command the first missions into space, the American public has had a rather glamorized, Hollywood cowboy image of those dashing, daring young men who pushed our boundaries in flight and space outward.

Ever since Tom Wolfe wrote The Right Stuff about those early Air Force test pilots who broke the sound barrier and went on to command the first missions into space, the American public has had a rather glamorized, Hollywood cowboy image of those dashing, daring young men who pushed our boundaries in flight and space outward.

The truth, which I have gleaned from many, many, many hours of interviewing at least the NASA pilots who were involved in those programs, is that cowboys were few and far between among their ranks. Oh, they all loved to fly. Even the NASA pilots were, almost exclusively, pulled from the military’s ranks. That’s where they got the skills and experience they needed to fly all those supersonic and unproven aircraft designs.

But there’s a difference between an adrenaline junkie and a thoughtful adventurer, and the pilots who flew the early X planes, like Bill Dana–and Neil Armstrong, and Milt Thompson, and Scott Crossfield–were almost all thoughtful adventurers. Most explorers who take on serious adventure challenges are. They have to be, if they want to survive the process. It’s easy to skydive or bungee jump with little thought, these days, and just enjoy the adrenaline rush. But if you’re the first person to see if those things actually work or if they’re going to plunge you to your death, it behooves you to think through all the components and risk factors very, very carefully. More so if you’re doing something like attempting to reach the South Pole, fly Mach 2, reach space, or fly an unpowered bathtub back from the edges of it safely for the first time.

I mention the bathtub because among his many achievements, Bill Dana actually did something pretty close to that.

From 1963 to 1975, NASA conducted flight research on a series of wingless vehicles, to see if a “lifting body” (or wingless craft that got its lift from the shape of its body alone) could safely fly back from space and land on a runway. The wingless shape was ideal for a spacecraft. But it obviously posed problems for control in atmospheric flight and landing. The craft were nicknamed “flying bathtubs” because of the round, stubby (and decidedly un-aerodynamic-looking) shape most of them had. And Bill Dana was one of the main pilots in that program. Here, below, is a photo of him, just after landing one of the vehicles, as he turns and watches the B-52 launch plane flying overhead the dry lake at what was then called the NASA Flight Research Center, on the grounds of Edwards Air Force Base, where the flight research was performed. (This past January, the Center was renamed the Armstrong Research Center, in honor of Neil Armstrong, who worked there as a flight research pilot and aeronautical engineer before becoming an Apollo Astronaut.)

NASA photo ECN-2203 HL-10

NASA photo ECN-2203 HL-10

The men who flew machines like this (and many others) were careful and calculating. They had precise test cards they followed to the letter and number. But doing anything for the first time is somewhat unpredictable. And while there are certainly risks to space flight today, the nation’s tolerance for losing humans in the process has decreased … well, astronomically.

The first 8 minutes of a Space Shuttle launch remained, until the end of the program, “the riskiest activity a human can undertake on planet Earth,” as one Space Shuttle commander described it to me. During those minutes, the failure of even one of some 800 critical pieces could cause a catastrophic explosion or fatal disabling of the spacecraft. But some of the riskier NASA missions contemplated, after the Challenger explosion in 1986, were cancelled because of that unacceptable risk. Today, it is not okay to lose astronauts and test pilots. In the 1960s and 70s, however, we were in a Cold War with the Russians, and aeronautical and space supremacy was seen as worth whatever risks it took. Fully one half of the early Atlas rockets tested and used on the Mercury spacecraft blew up or failed on launch. Those particular flights just didn’t happen to have people on board. But the program continued.

Accidents still happen, but in the test and research heyday of Bill Dana and his peers, they happened frequently. Scott Crossfield told me once he fully expected to die in the cockpit of the craft he was testing and exploring. Scott Carpenter once said something similar about how he approached the risks of the Mercury program. Pilots like Bill Dana, Neil Armstrong, and the others understood the risks. They and the teams they worked with did careful planning and tried to mitigate those risks as much as they could, just as Admiral Richard Byrd, Merriweather Lewis, Edmund Hillary and George Mallory undoubtedly did for all their earlier explorations. But if adventure of any kind is unpredictable, the adventure of exploration into the unknown represents the extreme version of that rule. Which means the risks can never be completely mitigated.

And yet, if I am saddened by Bill Dana’s passing, it was not because of his physical exploits or achievements. Those are impressive, to be sure. But while all adventurers and explorers have to possess some of the same qualities–a love of adventure, a certain level of mental fortitude, physical courage, resourcefulness and analytical problem-solving skills–they are not all alike in terms of personality and character. All of us undoubtedly know some very adventurous souls who are also very hard charging, self-absorbed, or have egos equal to their achievements.

Bill Dana was none of those things. What I remember about him was that he seemed such a gentle soul: humble, sweet, polite, and a very good listener. He was a thoughtful man who just happened to research and fly very difficult, very fast, and very high-risk aircraft and spacecraft.

There are those who explore and take on adventure for the sake of being able to say “I did that.” For the laurels of the achievement, or the status and image associated with that endeavor. (See, for example, many of the people who take on Mt. Everest with paid guides, instead of exploring an equally challenging but lesser-known peak.) I much prefer those adventurers (and in this I include adventurers of all kinds–physical, professional, and emotional) who take on the challenges of those adventures, quietly and without fanfare, for what I consider the better of reasons: because they believe it’s important. To themselves, to their families, or, as in the case of Bill Dana, for the sake of his country, and the safety of those who would follow in his footsteps.

Bill would be quite irritated at anyone who tried to call him a hero for what he did. Research and test flying was his job, and his skill, and risks came with the job. He would consider himself no more brave than a pediatric surgeon, a school teacher on the first day of school, or some of the widows he knew who had to carry on after their husbands were killed in the line of duty. We overuse the word hero to a nauseating degree, and I wouldn’t apply it to Bill, anyway. He was, instead, that rare combination of adventurer who managed at the same time to be a decent, kind, humble, considerate and admirable human being. You wouldn’t think that was so hard to be, or find. But it is.

There are few enough of those people in the world, and the world today has one fewer of them on it. And for that, I am sad. But I am glad, and deeply grateful, that I had the honor of knowing Mr. William H. Dana. And I am sure that anyone else who knew him would agree most heartily with that.

Very well said Lane!

We had lots of great pilots at Dryden, but in our lowly F-15 program, Bill was the very best at getting a difficult test point. Sort of like Fitz…..somehow, he just was able to cut through all the chaff and get it done…

Amen, Lane. I would add to your qualities, generosity and a wonderful sense of humor. Many of his fellow research pilots shared a sense of humor, but in his case at least, it included a willingness to laugh at himself. The real tragedy is not so much his death as his debilitating and long illness, which included loss of memory. He was truly a rare and wonderful person, as you recognize.

I am so happy to read such a wonderful and accurate tribute to Bill Dana. As an acquaintance in the town where he lived and raised his family I can vouch for his kindness, humility, and gentle manner. What an example, and terrific human being.